Island Stories:

![]() Danzig

Mine

Danzig

Mine

![]() Zeballos

Iron Mine

Zeballos

Iron Mine

![]() Conuma

Peak 1910

Conuma

Peak 1910

Alexandra Peak

Argus Mountain

Bate/Alava Sanctuary

Beaufort Range

Big Interior Mtn

Big Interior Mtn 1913

Part 1

Part 2

Bolton Expedition 1896

Cliffe Glacier

Clinton Wood

Comox Glacier

Comox Glacier 1922

Comox Glacier 1925

Comstock Mtn

Conuma Peak

Copper King Mine

Crown Mtn

Elkhorn 1912

Elkhorn 1949

Elkhorn 1968

Eugene Croteau

Golden Bullets

Golden Hinde 1913/14

Golden Hinde 1937

Golden Hinde 1983

Harry Winstone Tragedy

Jack Mitchell

Jim Mitchell Tragedy

John Buttle

Judges Route

Koksilah's Silver Mine

Landslide Lake

Mackenzie Range

Malaspina Peak

Mariner Mtn

Marjories Load

Matchlee Mountain

Mount McQuillan

Mt. Albert Edward

Mt. Albert Edward 1927

Mt. Albert Edward 1938

Mt. Becher

Mt. Benson 1913

Mt. Benson

Mt. Doogie Dowler

Mt. Colonel Foster

Mt. Hayes/Thistle Claim

Mt. Maxwell

Mt. Sicker

Mt. Tzouhalem

Mt. Whymper

Muqin/Brooks Peninsula

Nine Peaks

Queneesh

Ralph Rosseau 1947

Rosseau Chalet

Ralph Rosseau Tragedy

Rambler Peak

Red Pillar

Rex Gibson Tragedy

Sid's Cabin

Steamboat Mtn

Strathcona Park 1980's

The Misthorns

The Unwild Side

Victoria Peak

Waterloo Mountain 1865

Wheaton Hut/Marble Meadows

William DeVoe

Woss Lake

You Creek Mine

Zeballos Peak

Other Stories:

Sierra

de los Tuxtlas

Antarctica

Cerro del Tepozteco

Citlaltepetl

Huascaran

Mt. Roraima

Nevada Alpamayo

Nevada del Tolima

Nevado de Toluca

Pico Bolivar

Popocatepetl

Uluru/Ayers Rock

Volcan Purace

Volcan San Jose

Biographies

Island 6000

Cartoons

Order the Book

Contact Me

Links

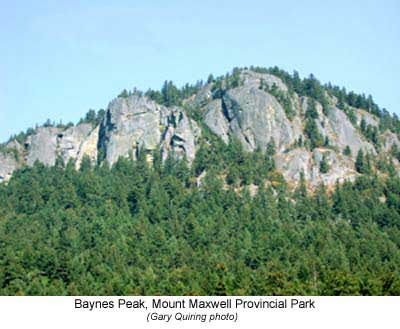

Mount

Maxwell [Baynes Peak]:

1922

Climb on Salt Spring Island

From the Daily Colonist September 10, 1922.

Climbing Face of Maxwell's Mountain, Salt Spring Island.

By Captain

Horace Westmorland

At the invitation of Captain Best of Ganges, Colonel Greer and I went to Salt Spring Island on August 18 [1922] to attempt to scale the 700-foot rock wall which forms the upper portion of the southwest face of Maxwell's Mountain, which is so clearly seen in profile as Fulford Harbor is entered from the sea.

On

Saturday, August 19, we motored from Captain Best's home at Ganges to

the Fulford-Burgoyne Bay Road and from Maxwell's farm had a good look

at the rock face. It appeared from this viewpoint that a way might be

forced up the cliff by a shallow scoop which terminates on the rock face

in a deeply cut chimney a few feet from the right of the main buttress.

Continuing to the Burgoyne Bay wharf, we had another view of our objective

from a different angle, and still the same chimney offered the best route

to attempt, affording, as it did, a possible way up the cliff at its highest

point. Other chimneys both to right and left of the main buttress would

have been an evasion of the rock face at its best, and we therefore decided

not to consider them at present.

On

Saturday, August 19, we motored from Captain Best's home at Ganges to

the Fulford-Burgoyne Bay Road and from Maxwell's farm had a good look

at the rock face. It appeared from this viewpoint that a way might be

forced up the cliff by a shallow scoop which terminates on the rock face

in a deeply cut chimney a few feet from the right of the main buttress.

Continuing to the Burgoyne Bay wharf, we had another view of our objective

from a different angle, and still the same chimney offered the best route

to attempt, affording, as it did, a possible way up the cliff at its highest

point. Other chimneys both to right and left of the main buttress would

have been an evasion of the rock face at its best, and we therefore decided

not to consider them at present.

Ascent Begun

Setting the aneroid down by the sea at zero, we struck into the bush by

a logging trail accompanied by Captain Best and two of his boys, who very

kindly carried our ruck-sac and climbing rope for us. About an hour's

steady walking took us to the broken ledges below the cliff and a few

minutes easy scrambling to the foot of the great wall, where we halted

for a rest and a sandwich before tackling the difficult part of the climb;

the aneroid here read 1,350 feet above sea level. After staving off the

cravings of the inner man, Colonel Greer and I roped up, and, taking leave

of our companions, who intended to return from this point. I took the

lead, and traversing round the foot of the main buttress, made two unsuccessful

attempts to lead up the initial 50 feet of rock face, but at a third attempt

a little further to the right was more successful.

Our great difficulty was the nature of the rock. The whole 700 feet of the cliff is "conglomerate" and the embedded pebbles and "cobble stones" came away when tested as holds in a most treacherous and disconcerting manner, and as heavy showers of rain had now commenced to fall, the whole surface of the rock was slippery. A few short pitches from ledge to ledge brought us to the foot of the shallow chimney we had selected from below. From here the leads were exceptionally long. Several times in succession the writer led out 85 to 90 feet of rope before reaching a stance from which he could be confident of holding the second man in case of slip.

Difficult Climbing

The type of climbing was unpleasant, there being a good deal of vegetation

in the back of the shallow chimney. This vegetation was alternately a

help or a source of danger, as it was, respectively, firm or loose. There

was also a prevalence of moss, which when cleared away, revealed only

smooth roundnesses and not the clean-cut holds we hoped for. Whenever

possible we employed the method known to climbers as "backing up,"

but for considerable distances the walls of our chimney were either too

indefinite or too far apart to permit of it. The leader found the long

length of rain sodden rope from his waist a serious handicap to balance,

and after a particularly steep 90-foot lead up the wet rocks it was a

relief to find the chimney cut deeply into the face of the cliff, forming

a narrow cave, on the sloping floor of which it was possible to lie down

in temporary safety and comparative comfort for a breather before singing

out the customary "Come on" to Colonel Greer and gathering in

the slack of the rope as he mounted slowly upwards to this airy haven

of rest.

On his arrival we studied the prospect before us. High above our heads the smooth wall of the chimney projected out over the shear face of the cliff. Direct progress upwards was barred by the overhanging roof of the cave, and though we thought it possible to overcome the difficulties of the chimney itself by back and knee methods, whether or not a way could be forced out of the cleft to the rock face either to right or left we could not foresee. From where we rested the true right wall appeared the more possible of the two, and when the second man had anchored himself facing the right wall, by bracing myself across the chimney and raising each shoulder alternately to gain a little height in the strenuous method known to mountaineers as "backing up," it was possible to progress slowly upwards. On this occasion the "backing up" was rendered a little more strenuous than usual by the overhang of the retaining wall. Some twenty feet of this brought me to the outside edge of the top of the chimney on a level with its roof, and if we were to succeed in our attempt an exit had to be made on to the rock face to the right or left. The right wall on which we had pinned our hopes proved to be unclimbable, wet and holdless. The left wall was more broken, though offering rounded and moss covered holds. However, twelve feet up the face, growing plucky in a crevice in the rock, was a sturdy little pine, affording a belay from which to manipulate the rope for the second man as he climbed the difficult chimney, and further, a safe starting point for the final pitches above. I therefore decided to endeavor to reach this tree.

Rather Hazardous

For this change of plan it was necessary to turn and face the left wall,

and in this exposed position, with inadequate holds, great care was required,

and even when the movement was completed position was only maintained

by bracing a leg across the chimney, not by any definite holds. I did

not envy Colonel Greer who was waiting below, doubtless wondering whether

or not the pitch would "go," and, if it would, why I did not

get on with it. Feeling that I would need all the intrepidity ascribed

to mountaineers by a certain parson during a sermon he preached in Keswick,

of all places, who likened the steadfastness required in the endeavor

of life to that "of the intrepid mountaineer who courageously climbs

upwards, cutting his steps in the roaring avalanche." I pulled myself

cautiously round the edge of the rock wall to the exposed rock face, and

by careful balance worked my way slowly upwards until I could thankfully

grasp the friendly pine and belay myself behind it. Greer then came up

in much better time, and victory was in sight, for only two problems remained

- steep rock face above us and then a short traverse to the right. A possible

solution of the steep face above us could be seen where great masses of

the conglomerate were split in huge poised blocks, but a closer inspection

showed them to be unsafe. I then tried a little to the right, but fifteen

feet up found the slippery holds inadequate, and had to descend. A few

feet to the left the rock was steep to the verge of overhanging, but there

were small holes here and there which looked firm. The situation was almost

Dolomitten in the sheerness of the direct plunge downwards of over 600

feet "as straight as a beggar can spit, " and the firmness of

those holds was comforting. Greer, looking upwards, could see little excepting

the well nailed soles of my climbing boots. Our friends below, just as

I was on the worst part, were calling anxiously, as they could not see

us in the driving mists, and I had the same sensation as a golfer when

someone speaks in the middle of his swing. Every faculty was required

to preserve balance or the slippery rocks, and the calls were a distraction.

The rope swinging from my waist dislodged a small piece of rock, which

struck Greer on the forehead, but, seeing my precarious position, and

having heard my muttered remarks on the subject of the people who shouted

unnecessarily, he with the self-restraint of a stoic, remained silent.

Excelsior!

The pitches had increased in severity as we climbed higher up the face,

but this was the last real difficulty, and after some thirty feet I was

able to crawl onto a safe resting place, a shelf of rock with a shallow

cave-like roof. Colonel Greer joined me on this shelf, and from it we

traversed to the right along a narrow ledge requiring a delicate touch

to the top of the cliff. The aneroid read just under 2000 feet. The rock

wall had given us a climb of nearly 700 feet, and we had taken over four

hours over it.

We announced success to our, by now anxious friends in a triumphant Engadine yell, coiled our hundred-foot Alpine Club rope, lighted our pipes, and with thoughts turning to hot tea swung along through the mists in a wide detour to avoid further contact with the cliff, and sloped down to Burgoyne Bay, where a most hospitable welcome awaited us, tea, bully beef and cucumber sandwiches being the much appreciated order of the day.

We were informed by the islanders that the face had not been ascended in the past, and we cannot recommend it as a rock climb in the future. The conglomerate is treacherous and insecure, and the cliff is excessively, steep and forbidding. We enjoyed the climb, for there is always joy in the successful overcoming of difficulties, and there is a curious sense of enjoyment to be derived from being wet through and very tired. A legend is told of an Indian maiden who stilled the flutterings of her broken heart by jumping from the top of the rock to the abyss below. Probably the cliff is better suited to that purpose than as a playground for cragsmen.

Addendum:

This feature had been named Mount Baynes c1859 by Captain Richards, RN,

and so-labelled on British Admiralty Chart 2840, 1861, however local residents

began calling this Mount Maxwell at about the same time, resulting in

the May 2, 1911 decision to adopt "Mount Maxwell (not Mount Baynes)".

Through correspondence with local authorities on Saltspring Island, it

was agreed in 1939 to designate the highest point on the landmass Baynes

Peak, and name the newly-created surrounding park Mount Maxwell Park.

The following information comes from British Columbia Coast Names,

1592-1906 by John T. Walbran. "[Saltspring Island] ...Captain

Richards when surveying here evidently wished to associate the island

with Rear Admiral Baynes, commanding at the time, 1857-1860, the Pacific

station, his flagship, staff and officers etc. He therefore named the

highest mountain Baynes, after the Admiral; Ganges Harbour after the flagship;

Fulford Harbour after the captain; Burgoyne Bay after the commander; Southey

Point after the admiral's secretary; Mount Bruce after the previous commander

in chief; and Cape Keppel after a friend of Admiral Baynes."

How to order | | About the Author || Links || Home

Contact:

Copyright ©

Lindsay Elms 2001. All Rights Reserved.

URL: http://www.beyondnootka.com

http://www.lindsayelms.ca